|

The 1994 measure specified that the work by inmates reduce the cost of prisons to the state

government. So, for example, 16 inmates sitting like telemarketers in office cubicles are answering

callers' questions to the Department of Motor Vehicles or the secretary of state's office, saving the

cost of state employees.

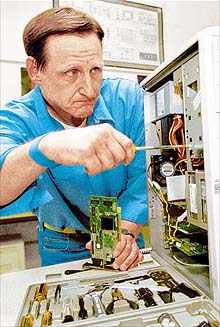

"What makes this so phenomenal," said Mr. Ragsdale, the inmate, as he assembled a computer, "is that

a few years ago a guy walking out of here had nowhere to go and no job skills, so they often ended up

coming right back to prison.

"At least here they had everything they needed: food, clothes, a bed and their friends."

Now, he said, "There is a waiting list to get into the class, and when guys are accepted, they have to

make a commitment to be on a team, or they are out, permanently, even for playing a computer game."

Signs already suggest that the Oregon program is working, state officials say. The percentage of inmates

admitted to Oregon prisons in 2000 who were returning parolees was only 25 percent, down from 47 percent

in 1995.

Inmate behavior in Oregon's 13 prisons has also improved, prison officials say. Because a disciplinary

report can lead to automatic expulsion from the most coveted work assignments — like the computer

program — there has been a 60 percent reduction since 1995 in major disciplinary reports, including

for fighting or attempted escape.

Also, because admission to some of the best prison jobs and classes

requires a high school diploma or its equivalent, Oregon's inmates

are now completing G.E.D.'s after an average of only 1.5 starts, down

from 8.5 starts before 1995. Over all, Oregon prisons have a higher

rate of G.E.D. completion than the 17 community colleges in the state

that offer the instruction, Mr. Ickes noted.

But Oregon has not yet found a way to gauge perhaps the most important

measure of the success of its new program — how quickly inmates find

jobs and how long they hold them. It has been difficult getting money

from the State Legislature to set up a tracking system, prison officials

say, though they hope to have a system in place soon.

Finding ways to ease the return to society and reduce recidivism "is

the hot topic in the criminal justice system, because of the huge

costs and numbers involved," said Michael Jacobson, a professor of

criminology at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and a former

director of New York City's Department of Correction.

About 614,000 people will be released from state and federal prisons

this year, said Allen J. Beck of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the

statistical arm of the Justice Department. Within three years, based

on studies he has done, Mr. Beck said, 62 percent of them will be

arrested again, and 41 percent will be sent back to prison.

In California alone, Professor Jacobson said, about 70,000 people, 75

percent of the state's total number of parolees, are sent back to prison

each year for parole violations, like failing drug tests, for periods

averaging five and a half months. These inmates take up about 20 percent

of all the state prison beds each year, he said, costing California

$1 billion.

| |